What is the RSSB doing to ensure Great Britain’s rail is on track to be net carbon zero by 2050?

Posted: 20 February 2020 | Andrew Kluth | No comments yet

For our ‘Improving Rail’s Environmental Impact’ series, Andrew Kluth, Lead Carbon Specialist of Sustainable Development at RSSB, explains the scope of the ongoing research and development necessary to address Great Britain’s rail challenges of decarbonisation and removing diesel-only trains from the railway.

In June 2019, the UK Government committed to a national target of net-zero emissions by 2050. This demands radical change from all sectors of the economy.

In July 2019, the Rail Industry Decarbonisation Taskforce published its final report setting out a vision for how Great Britain’s railway will contribute to this target. The Taskforce had been set up in early 2018 following the challenge set by Jo Johnson, the Minister for Rail at the time, for the industry to remove diesel-only passenger trains by 2040 and set out a vision for how it will decarbonise.

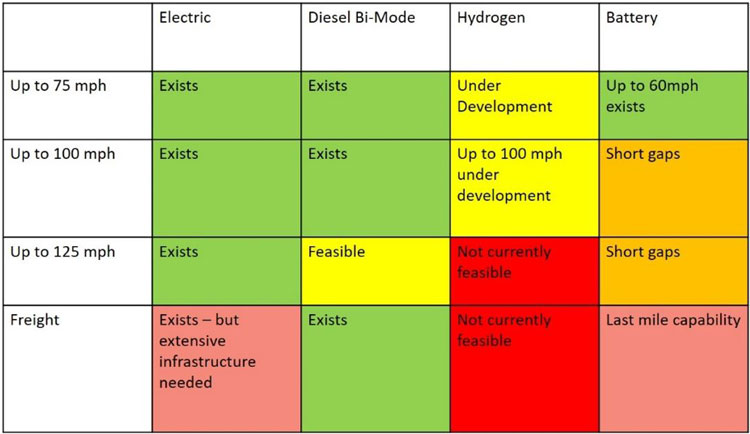

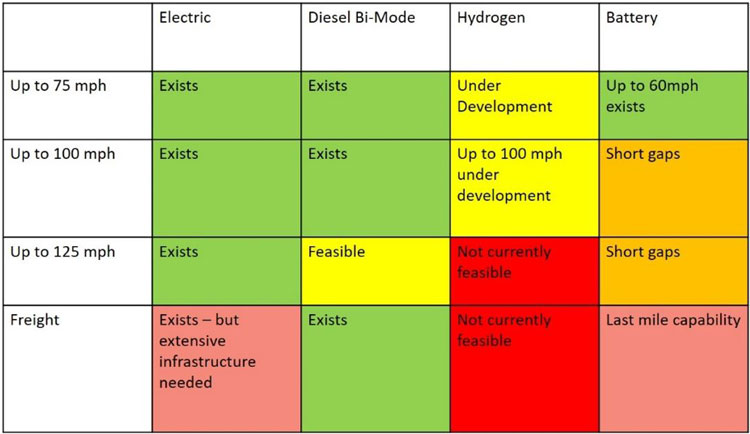

The challenge was not whether operational decarbonisation was possible – this could be done by electrifying the whole network – but whether it could be done in a cost-effective manner. The Taskforce concluded that it would be possible to remove diesel-only passenger trains by 2040 and contribute to the 2050 target in a cost-effective manner through a balanced mix of electrification alongside the introduction of hydrogen and battery trains.

This conclusion was drawn from considering a wide range of views and evidence from across the industry, as well as the findings of a research project commissioned by the Rail Safety and Standards Board (RSSB), which examined which traction options were likely to be sufficiently mature by 2040 to be able to contribute to a low carbon railway. It was determined that hydrogen and battery trains could deliver most services currently delivered by diesel trains with maximum speeds up to 100mph.

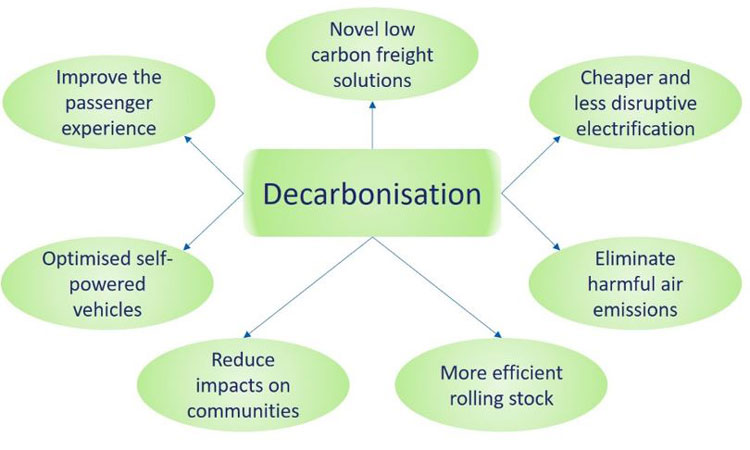

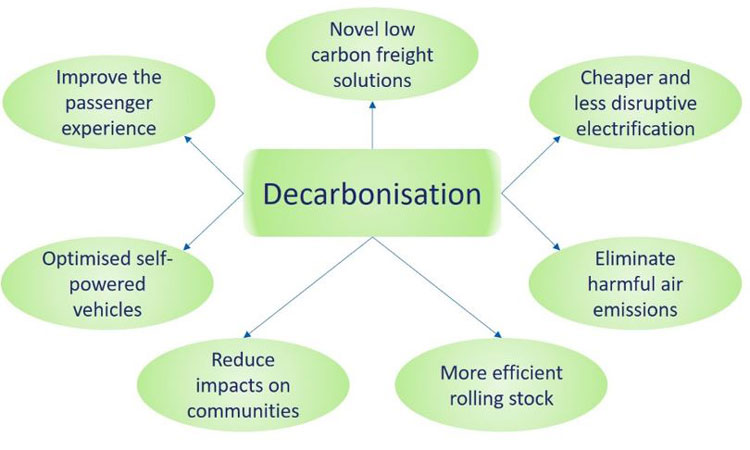

Rail decarbonisation has its own direct benefits. In addition, it will deliver benefits in related areas that will also have economic, environmental and social value.

RSSB has supported this work throughout, both by providing the secretariat and technical leadership for the Taskforce, and by developing and managing research projects, such as the one just described, to answer key questions.

In summer 2019, following the publication of the Taskforce final report, RSSB launched the DECARB programme, the core of which is a series of linked projects to implement specific recommendations made by the Taskforce.

1. To define the rail industry’s carbon footprint and system boundary for carbon measurement, management and reporting

This was estimated in 2009, so a core objective of this work is to revisit the previous work, revalidate it where appropriate, and update and extend it where necessary. The main purpose of this work is not so much to agree a total emissions figure. The major component of this – the energy used to power trains and the infrastructure to deliver that energy – is already well understood and reported. The most important outputs will be to identify and agree emissions sources across the rail sector, set a system boundary in line with agreed carbon management and reporting standards, and to identify the ‘guiding hands’ best placed to lead on emissions reductions from various sources.

2. To determine the main components and projected costs for the battery and hydrogen infrastructure necessary to support these as traction options in trains

We know that there is at least one solution to decarbonise the railway – electrification. We need to develop robust comparative whole life, whole system costs of other traction options to determine which is likely to be the most cost-effective solution for the service demands on different parts of the railway. This will be fundamental to delivering the railway’s decarbonisation target at the lowest cost through a combination of low carbon traction options, combined with efficiency improvements across the system.

3. To develop appropriate targets, both long-term and intermediate, for the industry to work towards

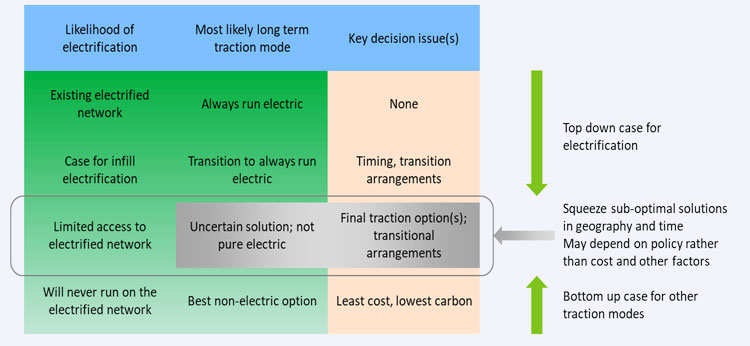

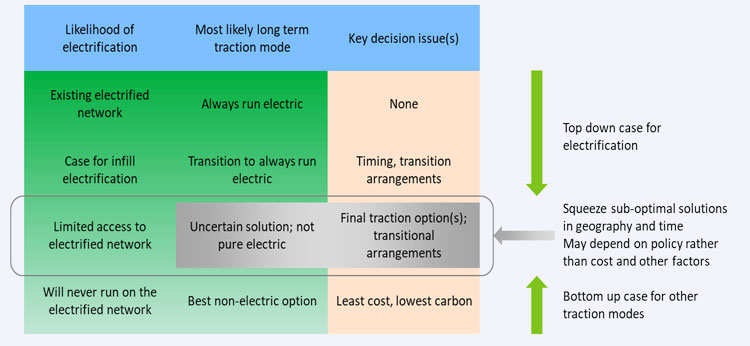

While the 2050 target is clear, the challenge for decarbonisation is as much about pathways to decarbonise and how quickly decarbonisation should be implemented. There are internal and external factors to consider. For example, when should existing diesel trains be removed from service to achieve the most cost-effective transition? There are up to 2,400 vehicles – including around 1,200 Sprinters, which run services up to 100mph – due to reach 40 years of service life in the late 2020s and early 2030s. They will need to be replaced by appropriately tractioned vehicles, depending on which areas of the network will be electrified and when, and which will need self-powered vehicles. The final traction options and any interim arrangements will have significant impacts on the cost profiles of different decarbonisation pathways. The railway will also need to show that its carbon impact, compared with other transport modes, remains sufficiently low to justify investment in the railway as the preferred transport option.

4. To research how the objectives and incentives for major bodies and organisations integral to the decarbonisation of the railway may be aligned to deliver decarbonisation as a core business objective in the most cost-effective and efficient manner

Until recently, rail’s status as the low carbon transport option for certain types of journeys has simply been accepted as being an integral aspect of the railway’s basic operation. The industry has, therefore, not been under pressure to consider carbon as a key performance measure. However, rail’s status as the low carbon option will be threatened by the decarbonisation of the automotive sector, which can move at a greater pace than the railway’s long asset lifecycles can replicate. There is a need to ensure that all aspects of rail decision-making – from long-term policy, financing, strategic planning and detailed planning around rolling stock procurement and infrastructure development – are aligned as part of the major structural reforms that are anticipated for the rail industry.

The solutions for passenger rail, while presenting significant challenges, are nevertheless easier to envision than is possible for rail freight. The demands of rail freight traction are such that only electrification and diesel traction are possible within the constraints of freight operations on Great Britain’s rail network. Any lower carbon future for rail freight will probably have to rely on a range of incremental solutions, particularly where electrification is not possible.

There is increasing confidence that a balanced mix of electrification, battery and hydrogen traction will be able to meet service demands of all main classes of passenger trains. The demands of freight still remain a challenge.

RSSB has commissioned a project to consider what solutions, regarding both traction options and other interventions, will enable substantial carbon reductions in the rail freight sector. These will include the marginal benefits and costs of electrifying key freight routes and engine emissions improvements, such as by: co-firing diesel with lower carbon fuels; hybridisation of freight locomotives; opportunities to lengthen at least some freight trains to allow for the possibility of battery and hydrogen traction in some circumstances; and freight prioritisation when the opportunity arises.

RSSB is supporting a parallel programme to develop a rail air quality strategy. Carbon is ubiquitous, whereas air quality concerns tend to be more localised and more immediate. In general, emissions reductions will contribute to the delivery of both decarbonisation and air quality objectives. It is possible that the more immediate changes that could be achieved on air quality, such as the establishment and expansion of clean air zones in urban areas, could impact on the most cost-effective decarbonisation pathways.

Any changes to deliver decarbonisation will have fundamental impacts and interdependencies across the whole rail sector. It is inevitable that compromises will have to be made. The best low carbon solution for one part of the industry will not be the best solution for another part. For example, smoothing journeys for freight trains to reduce the emissions from frequent stop-start movements could have impacts on the carbon and operational performance of passenger services.

The decisions necessary to achieve the best overall solution will need to be based on objective and impartial evidence. In turn, these decisions must be built on research which engages the whole industry in a transparent and inclusive manner to balance competing demands and priorities. Some commentators have argued eloquently that electrification to the greatest extent possible is, in the long run, the best solution from a whole life, whole system perspective.

The basic strategy is to implement the least-cost low carbon solutions where these are clear and to eliminate areas of uncertainty as soon as possible.

Future research to support this deliberative process will need to consider further questions. Some of these will impact not only the rail industry, but also other sectors. For example, if the railway sources energy from locally-generated renewable sources, how can this system be developed in a manner that allows it to contribute to supporting the decarbonisation of national power supplies generally? How will the rail sector source hydrogen and could the consistency and reliability of rail hydrogen demand contribute to stimulating the development of a wider hydrogen sector? How can third rail electrification, where this is established on Great Britain’s rail network, be updated to meet 21st century demands on a low carbon railway? How can new-build, refurbishment and improvement projects for stations and depots, as well as major infrastructure projects, best reduce whole life, whole system carbon impacts?

The cooperation and support that the Rail Industry Decarbonisation Taskforce was given in formulating its recommendations, and the positive manner in which they have been received, reflects the commitment Great Britain’s rail sector has to delivering decarbonisation within the demanding timeframes necessary to meet national and global deadlines. The Taskforce report set out a high-level response to the challenges of decarbonisation and removing diesel-only trains from the railway.

This article has indicated the scope of the ongoing research and development necessary to address the detailed questions that must now be answered.

Andrew Kluth joined RSSB in May 2018 to support the Rail Industry Decarbonisation Taskforce. He was the technical author for the Taskforce’s report to the Minister for Rail, and now works on implementation of key recommendations. He has over 30 years’ experience in environmental and sustainability roles, across transport and logistics, construction, civil engineering, natural resources, retail and media, having been based at various times in the UK, Hong Kong, Liberia and Singapore. Andrew has degrees from Liverpool and Bath Universities, once held a patent for a very efficient irrigation device and was appointed a Fellow of IEMA in 2018.

Related topics

Cargo, Freight & Heavy-Haul, Diesel Locomotives, Rolling Stock Orders/Developments, Standardisation & Technical Harmonisation, Sustainability/Decarbonisation