Pitching for Railway Investment?

Posted: 10 April 2018 | Martha Lawrence, Nicolás de León de Mariá | No comments yet

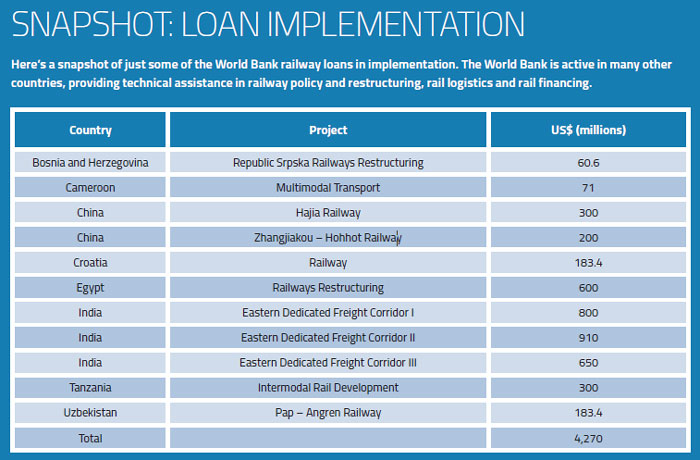

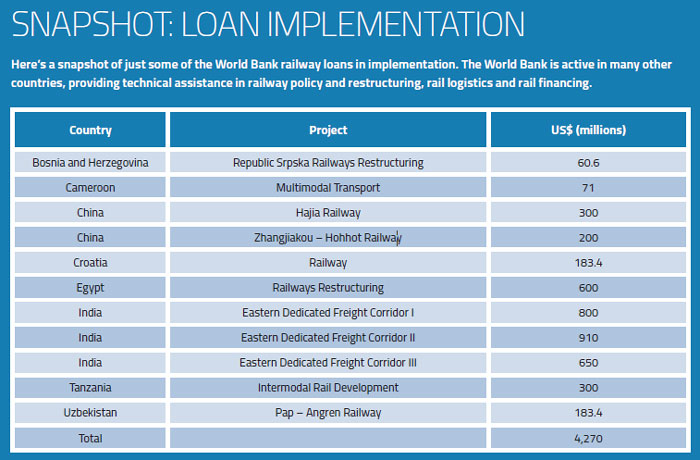

As railway experts working for the World Bank, Martha Lawrence and Nicolás de León de Mariá engage with many client countries that are looking to expand or upgrade their railway systems. For Global Railway Review, Martha and Nicolás explain that whenever a railway investment is pitched to them, their first question is always: “What are your trains going to carry?” They ask this question because it is fundamental to railway financing.

Railways are very capital intensive and increasingly need to attract financing from the private sector to ensure success. That is why the World Bank recently updated its Railway Toolkit1 to include more information and case studies on railway financing. Here, in a nutshell, are the key lessons about railway financing from this update.

What is financing?

Financing is the process of converting future cash flows into money that can be used for investment now. Let’s look at a typical railway investment project. The project requires a big investment up-front. Over time, the project has revenues and operation and maintenance costs. The revenue is (hopefully) more than the operating cost, so the project generates positive cash flows and profit over time. Financing is the mechanism for converting the profits from later years into money that can be available now, so that the railway can make an investment. Financing is not free money – it must be paid back, with interest or dividends added.

What is funding?

Funding is the revenue stream that pays back the financing. It is the foundation that makes financing possible. Funding may come from passenger ticket revenues, freight revenues, subsidies from the government to provide social services or revenues from leveraging assets such as stations and right-of-way. That’s where the question of “What are your trains going to carry?” comes in, as it will allow us to identify the source(s) of funding, which in turn can lay the foundation for a solid financing plan.

Funding gap

Sometimes the future funding will not be enough to pay for the needed investment – in which case the railway is left with a ‘funding gap’. To close the gap, the railway can:

- Reduce investments and/or operational costs

- Increase revenue by expanding profitable traffic and/or obtain subsidies from the government for providing loss making services.

In many railways, strategies to reduce the funding gap rely mostly on the core railway business, with actions to increase revenue and decrease costs. PKP Cargo, the Polish railway’s freight operator, is an example of such a successful restructuring process. In 2011, PKP Cargo was losing market share due to liberalisation of the market and entry of new players, so large-scale restructuring and optimisation was necessary to remain competitive. Key measures included:

- Employment optimisation to reduce labour costs and improve productivity

- Re-organisation of rolling stock management to increase efficiency and drive down costs

- Long-term contracts with strategic clients

- Modern standards in cost management and financial control

- In 2013, 50 per cent of the stock was floated in an IPO on the Warsaw Stock Exchange, raising over $500 million.

Some railways own assets that can be used for activities beyond railway operations. For example, many railways have stations in desirable urban areas with high real estate value. Redeveloped, attractive ‘new’ stations bring an enhanced customer service experience and a greater integration of railway and service industry business. This often results in higher profitability of the stations due to the creation and revitalisation of businesses and cooperation with the community and vendors. Some good practical examples include JR East, whose non-railway business revenue increased from seven per cent in 1987 to 34 per cent of total revenue in 2011; or Tokyu Corporation, which had had an increase of 65 per cent of total revenue related to non-transportation services in 2017. Selling air rights – building a platform above a rail yard or active tracks – to allow construction of buildings is another way to benefit from real estate. For example, the Barclays Center in Brooklyn, New York was constructed above the Vanderbilt train yards belonging to the adjacent Atlantic Terminal station.

Railway right-of-way and communication assets may also be leveraged. For example, in India, Indian Railways allowed the communications company Railtel to use its right-of-way to lay telecommunications lines in return for use of four out of 24 fibres for rail train control and communications and seven per cent of the generated revenue. Railways may also sell space on the electrification network for power cables of other users.

If it successfully closes the funding gap, the railway will be able to attract private sector financing through many structures and instruments. Thus, the most effective action that a railway or government can take to attract private sector financing is to adopt policies to close the railway’s funding gap.

Risk

When the private sector looks at a financing opportunity, it will examine potential risk very closely and build its risk perception into the cost of providing the financing. In my experience, two of the risks that investors take most seriously relate to the governance of the railway sector as a whole and the corporate governance of the railway company itself.

Sector governance

On sector governance, the private investor wants to know: “If I invest in this railway or this project, will the government change the rules of the game in a way that reduces the funding that is supposed to pay back my investment?”

Corporate governance

On corporate governance, the private investor will ask: “Does the governance structure of the railway company ensure that it will take commercially viable/sensible decisions that will support its ability to pay back investors?” To keep the cost of financing low – and, indeed to access private sector financing at all – these governance risks must be addressed to investors’ satisfaction.

The Barclays Center in Brooklyn, New York has been constructed above the Vanderbilt train yards belonging to the adjacent Atlantic Terminal station

Public-private partnerships (PPPs)

PPPs are best thought of as a project delivery mechanism with a financing component built into it. PPPs in railway can be very effective when:

- The private sector brings a skill that the railway lacks

- The private sector can manage the construction or operation of the project more efficiently than the railway

- PPP creates incentives for service and market development that would be otherwise lacking.

If only financing is needed, PPPs may not be the best option, as they are complex to design and tender and require ongoing capacity to supervise effectively.

‘Maximizing Finance for Development’

In September 2017, the World Bank launched ‘Maximizing Finance for Development’ which seeks to crowd in private financing for developmental needs. For railways, financing will be maximised by policies to address the funding gap and mitigate risks through transparent, robust sector and corporate governance. With these interventions, the railway can access many private sector financing instruments – loans, bonds, equity, leasing – as well as consider PPP as a project delivery mechanism with financing.

Remember, always ask: “What are your trains going to carry?”

Reference

- The new edition of ‘Railway Reform: A Toolkit for Improving Rail Sector Performance’, with new material and case studies on financing, sector governance and corporate governance of state-owned enterprises, can be found at the PPIAF website (https://ppiaf.org/ppiaf/sites/ ppiaf.org/files/documents/ toolkits/railways_toolkit/ index.html) or from the World Bank’s Open Learning Campus http://documents. worldbank.org/curated/ en/529921469672181559/ Railway-reform-Toolkit-for-improv ing-rail-sector-performance.

Biographies

Stay Connected with Global Railway Review — Subscribe for Free!

Get exclusive access to the latest rail industry insights from Global Railway Review — all tailored to your interests.

✅ Expert-Led Webinars – Gain insights from global industry leaders

✅ Weekly News & Reports – Rail project updates, thought leadership, and exclusive interviews

✅ Partner Innovations – Discover cutting-edge rail technologies

✅ Print/Digital Magazine – Enjoy two in-depth issues per year, packed with expert content

Choose the updates that matter most to you. Sign up now to stay informed, inspired, and connected — all for free!

Thank you for being part of our community. Let’s keep shaping the future of rail together!