Researching the significance of ballast in track degradation

Posted: 24 July 2017 | Graham Ellis | No comments yet

Our regular contributor, Graham Ellis, discusses track degradation and some of the research that is currently being undertaken to understand the significance ballast when it comes to track wear.

I recently attended the Stephenson Conference, at the Institution of Mechanical Engineers Head Office in London, for rail researchers and practitioners from across the world. A part of that conference included several sessions on rail wear and highlighted problems that I was not aware of, specifically rail wear caused by ballast flight.

A paper produced by Messrs Clarke and Prescott from the Resilience Engineering Research Group at the Faculty of Engineering at the University of Nottingham (UK) studied the factors that influence track degradation on the UK rail network. They identified that Network Rail (the UK’s rail owner and infrastructure organisation) spent £10.228 billion in 2014/15 of which £887 million was spent on track renewal and £501 million on maintenance across the 29,800km of track in the whole network.

As readers of Global Railway Review, I’m sure you’re all aware that managing railway infrastructure is a complex operation with lots of different pressures to keep the track fully operational, and one of the key requirements is to maintain the track geometry to ensure both safe and smooth travel. The track geometry worsens with usage and maintenance is required once track quality reaches an undesirable state.

Looking at the track, it consists of the subgrade, ballast, sleepers and rail. As trains traverse the track, the forces of the train cause plastic strain to occur in the ballast and subgrade which leads to uneven settlement.

Once this occurs, speed limits have to be imposed to protect the trains from potentially derailing and, initially, to ensure that passengers encounter a smooth ride. An in-depth analysis of all track wear factors identified that track speed, sleeper design and rail joint types were the primary factors in rail geometry degradation, but further analysis shows that a dirty ballast is also a factor in track degradation.

A separate paper from Professor Chris Baker at the University of Birmingham (UK) Centre for Railway Research and Education and Professor William Powrie at the University of Southampton, assisted by co-authors, examined something called ballast flight. Apparently as train speed increases it has been found that ballast from the track is being picked up and thrown along the underside of the train. Some of this ballast then lands on the top of the rail and is crushed by the passing train wheels causing pitting to the rail head.

Pictures of this rail head damage are shown in the pictures below (which have kindly been permitted to be used by Professor Baker to illustrate this article). You will see that there is significant pitting of the rail head where the ballast has been crushed in and this appears to be getting worse with increased train speeds…

Pitting in the rail head caused by crushed ballast

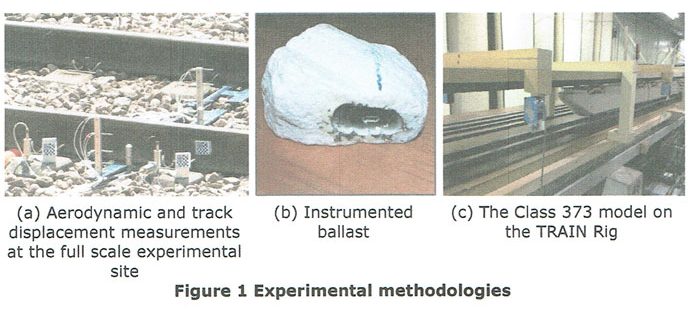

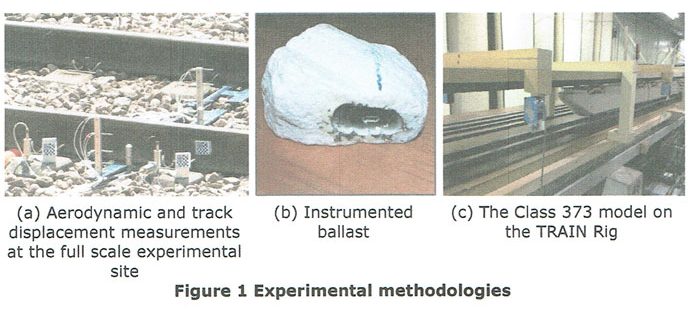

The way in which the research has been carried out was innovative, Professor Baker took a high-speed train model and inverted it over a track so he could measure the turbulence under the train set utilising a scale model of an HS1 class 373 Eurostar train.

The track was also instrumented to measure how the ballast behaved with passing traffic and a small piece of ballast was created so that actual movements could be measured; this is shown as item (b) above.

The conclusions from this work are that the ballast’s vertical acceleration, and thus its propensity to lift off, is largely due to the track displacement beneath the trains wheelsets and once the ballast is airborne, aerodynamic forces play a part in its direction of travel.

Importantly, the moving model technique used by the University of Birmingham produces accurate results that are in correlation with full scale values measured at the test site and is therefore a useful tool for homologation of new trains.

Global Railway Review Autumn/ Winter Issue 2025

Welcome to 2025’s Autumn/ Winter issue of Global Railway Review!

The dynamism of our sector has never been more apparent, driven by technological leaps, evolving societal demands, and an urgent global imperative for sustainable solutions.

>>> Read the issue in full now! <<<