Rolling stock – where is it heading?

Posted: 14 February 2017 | | 6 comments

Regular Global Railway Review blogger Graham Ellis provides a general overview of rolling stock developments and highlights the importance of renewing infrastructure in order to keep up with locomotive advances.

Aeroliner 3000 drawing

Over the Christmas and New Year period I had the luxury of catching up on my reading, in particular I got to read a number of fiction books on railway related stories. These books were by Edward Marston telling the stories of Robert Colbeck of Scotland Yard “Railway Detective” based in the 1800’s, one by Andrew Martin telling the story of Jim Springer the steam detective in the Edwardian era and finally Stephen Done’s Inspector Vignoles series set in the late 1940’s and based on the Great Central Railway. One thing that all of these books have in common, is that they contain very detailed descriptions of both the rolling stock and its supporting infrastructure.

In the books there are descriptions of the very earliest steam locomotive and carriages, moving through to some of the technical advantages that developed in the late 1880’s and early 1900’s and looking at the austerity forced on the railway companies by the two world wars and the need to continue austerity for far longer than anyone had previously anticipated. At the same time I was enjoying my reading, the BBC published a report prepared by the Press Association looking at the age of the rolling stock in the UK and decrying the fact that average age of this was 21 years. This made me think about where our railways and its infrastructure are heading and to start looking at what the rest of the world were doing.

My research about European rolling stock showed some discrepancies in the data produced; the EU believes that the average age of UK rolling stock is only 15 years compared to the European average of 30 years. I have spoken to a rail vehicle design specialist and director of innovative transport technologies and he tells me that he would be looking for a 30-35 year lifespan of the primary structure, with a number of refurbishments throughout that period.

That is therefore the benchmark most people are looking at but, this seems to apply more to Diesel and Electrical multiple units rather than locomotives. Looking at diesel locomotives it is clear that some are of significant age, the Class 37 locos used by DRS are well over 50 years old and the HST125’s used across the UK are all over 40 years old and with the delay in electrification of the Great Western Mainline it is likely that these power cars will be in service for at least another 10 years. There is no problem with this as long as people realise that these are expensive assets to buy and maintain and you cannot just lease them for three years like a car and then give them back, the lease need to be at least 10 years long to get a reasonable lease hire rate. Taking a look at electric locos I found that the East Coast Class 91 (HST225) is also fairly elderly in that the youngest is 26 years old and the most elderly is 29 years old.

Looking at passenger rolling stock, it is clear that major investment is going into this area of the business. According to industry figures, at least 940 train sets are being purchased consisting of 5,580 individual cars. These trains are being purchased for various franchises such as ScotRail, Trans Pennine Express, Great Western Railway, South West trains etc. In fact on a recent visit to London I took a photograph of the latest series 707 train stabled at Clapham Junction prior to the completion of driver training and installation onto the Windsor line.

What is surprising though is the number of units that are still going to be diesel powered, all of the Great Western Intercity Express Programme (IEP) trains are now being specified as bi-mode rather than a mix of electric and bi-mode due to delays in completing civil engineering works along the Great Western Line, in fact I reported on this delay in my last blog of 2016. As an engineer my all-time hero is Isambard Kingdom Brunel; who built the Great Western Mainline; and I am sure that he would be appalled that in this day and age we still cannot get our engineering act together to meet operational requirements. Without the infrastructure in place new rolling stock just cannot operate, this was experienced some years ago by South West Trains when the then “new” Desiro stock was introduced and it was found that the electrical supply could not meet the required loads. A massive investment programme was needed to upgrade the power supply to cure the problem, now we are ordering bi-mode trains instead of full electric because the infrastructure is not going to be built in time. This sounds like a slight problem but, with train replacement delayed the cascading of older stock to other train operating companies is also delayed and rolling stock far beyond its planned operational life is having to be retained as well as the extra cost of having to order bi-mode trains instead of the original electric units.

The Great Western was always going to have to operate some bi-mode units as the track to the West Country from Westbury and Bristol was not in the electrification programme. The track is however likely to suffer from higher wear and damage as the bi-modes are heavier than their pure electric counterparts and the HST 125’s, it is expected that in diesel mode they will probably be slower than the forty year old HST125 stock they are replacing, causing timetable problems and possible extended, rather than shortened journey times.

What we need to do now is to diarise the fleet replacement programme for the future along with the necessary infrastructure works so that we do not have to face the shall we/shan’t we decisions that have been forced on the industry this time around.

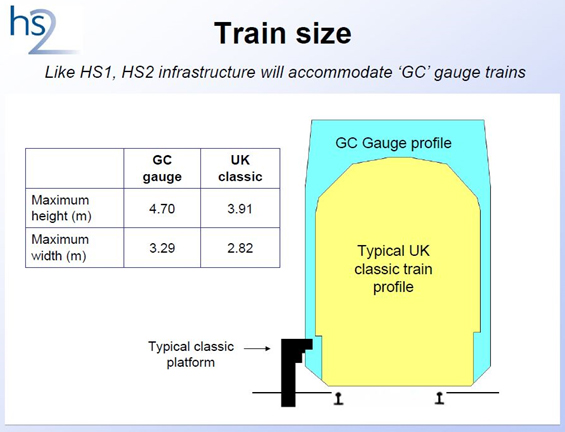

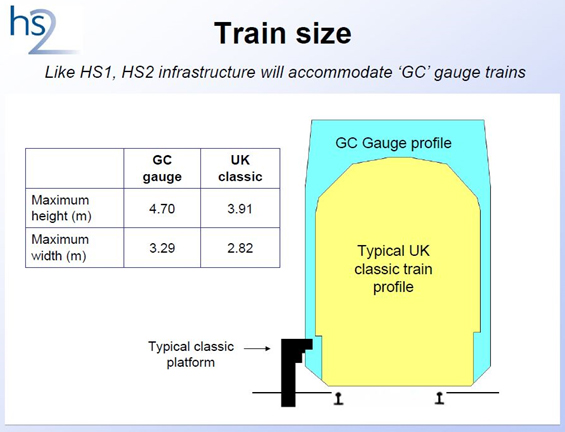

One idea that I have not yet talked about is the double-decker concept that is widely utilised on the continent. There is a proposal floating about from THJV, which is a joint venture between TSP Projects and CH2M, to introduce a double deck train that could work the outer London and further afield routes. The train has been designed by Jan Plomer who works as a train designer but, I think that there may well be a problem as he needs to achieve a cleared height of 4500mm when the largest gauge I can see, which is issued by the Rail Standards Safety Board, only allows a maximum height of 3910mm. This means major infrastructure alterations have to be undertaken to achieve the desired operating height and this ignores overhead wire clearances etc.

I would be interested to hear from Jan how he thinks we could achieve this in a cost-effective manner whilst still maintaining our intense daily train operations. Perhaps this is something I can come back to in a later blog.

D-DART concept design from Jam Plomer (THJV)

UK Train clearance guide

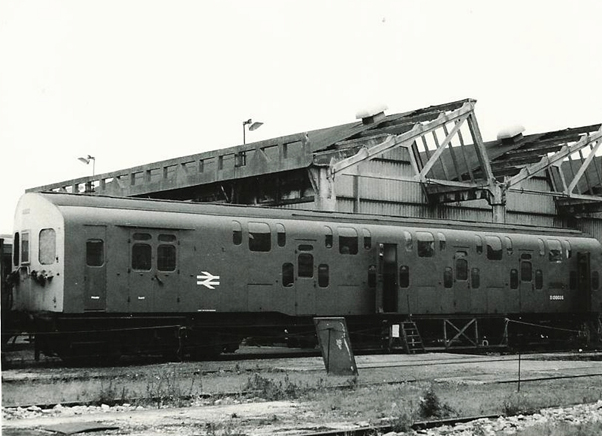

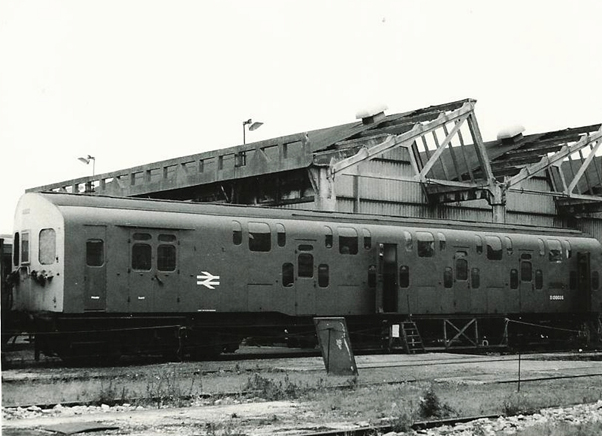

I am not against double-deck trains as I often use them in Europe and get a fantastic view of the countryside form the upper deck but, they are running at much higher gauge clearances than the UK, however I have found a picture of a Southern Region double deck train, Class 49 that was in service from 1948 to 1971.

SR Bulleid Class “4-DD” 750v dc 3rd rail 4-car double deck inner commuter emu No.4902 (later No.4002) in Rail Blue with all yellow front end at the Ashford Steam Centre, 10/72. Copy courtesy of Hugh Llewelyn.

I am also aware that another double-decked train was exhibited at InnoTrans in Berlin and this was produced within the UK loading gauge. This design is the Aeroliner 3000 designed by Andreas Vogler Studios of Germany for the Rail Safety and Standards Board. A full scale 9 metre long demonstration carriage was on the stand of the German Aerospace Centre (DLR). DLR is currently doing welding probes of the body construction with TU Dresden. Vogler are looking for partners to help bring the idea on the UK market, next step should be built a running prototype, even by converting an existing coach.

On a recent visit to London I spotted one of the new Siemens class 707 trains stabled at Clapham Junction. The class 707’s are due to be introduced into service on the Waterloo to Windsor line relieving older stock for other uses, there are 30 sets due for delivery and each is a five-car rake. I did however get a whisper from train staff that not all is going smoothly and that the first set was vandalised whilst at Clapham Junction.

Class 707, 707003 on the Clapham sidings

OUT NOW: The Definitive Guide to Rail’s Digital Future

The rail industry is undergoing a digital revolution, and you need to be ready. We have released our latest market report, “Track Insight: Digitalisation.”

This is not just another report; it’s your comprehensive guide to understanding and leveraging the profound technological shifts reshaping our industry. We move beyond the buzzwords to show you the tangible realities of AI, IoT, and advanced data analytics in rail.

Discover how to:

- Optimise operations and maintenance with real-time insights.

- Enhance passenger services through seamless, high-speed connectivity.

- Leverage technologies like LEO satellites to improve safety and efficiency.

Featuring expert analysis from leaders at Nomad Digital, Lucchini RS, Bentley Systems and more, this is a must-read for any rail professional.

I accept that AEROLINER300 rolling-stock proposed for HS2 routes incorporates (Am I correct?) tilting technology which compromises available width in its upper saloon, yet remains more space-efficient than Gallery Railcars used overseas. That said, Aeroliner300’s clever use of the Interlocking-Deck concept effectively ‘rules back in’ the operation of Bi-Level trains on UK soil. Surely the upstairs seating configurations of Aeroliner300 could be ‘tweaked’ to suit lower speed/multi-station operations e.g. 3-abreast seating with a passageway on either side. Walking (As opposed to standing)headroom may be a little tight with regards to arch-roofed carriages that UK’s overall structure-gauge dictates. But one eventual revision to UK’s infrastructure capable of effectively resolving this issue more than adequately is electrification of remaining Diesel lines (or, at least, advance upgrades to arched bridges). Had Oliver Bulleid incorporated a level passageway, thus step-accessed individual seating booths, his DD4 concept might still enjoy a following today. This, incidentally, marked the downfall of Mann Egerton and Crellin Duplex buses/coaches. Talking of which, Bristol/Dennis missed an oportunity to promote ‘interdecking’ by introducing 4-abreast/one side-passageway upstairs on their Lodeka/Loline respectively. But, by no means, are UK-operated non-tilting bi-level trains dependent on upgrades to its infrastructure nor need they be captive to any one route.

In the U.S., two Northeast Corridor (Boston-Washington) commuter operators run bi-level cars that fit through low-clearance NEC tunnels and under bridges. While to too-heavy U.S. rail cars are probably infeasible to operate in England and Europe, they may at least provide a model for design of more suitable bi-level cars.

It’s a travesty to describe the Bulleid 4DD as a double-deck train. The two decks were intertwined with the foot wells of the passengers on the top deck intruding into the head space of passengers on the bottom deck, so that passengers had the foot well of upstairs in their faces. You have only to look at the windows to see the problem. These trains were scrapped long before I learned they had ever existed – apparently they were a nightmare to board and leave, causing delays on busy commuter routes.

My interest is Baltic States railways and (obviously due to their former existence as part of the Soviet Union) to a lesser extent, the railways of Russia and the former USSR.

Lithuania runs modern EJ575 double deck electric trains built by Škoda Valgonka between the capital city Vilnius and the second city Kaunas, and also between Vilnius and Trakai. The loading gauge is huge, and allowed for massive steam freight locomotives which were 17ft tall, so tall that I have read that the overhead electricity has to be switched off when one of these brutes passes under wires with a tourist special. By comparison, a British 9F is only 13ft 1in tall.

That extra four feet allows a proper upper deck to be inserted into the EJ575 without restricting the headroom of passengers on the lower deck. That headroom is also helped by the lower deck being in a well between the bogies. Floor to ceiling height on the bottom deck is 2008mm 6ft 10in and on the top deck 1985mm 6ft 6in, so most passengers won’t have any difficulty walking in the trains. Obviously there is a staircase from the wide double-door entrances into a large lobby (two for each of the three cars) which needs to be surmounted, but it’s unlikely to take much longer to load than our trains with their single doors.

Further to my post yesterday about double-deck trains, there’s an interesting picture on http://transportingcities.com/2016/09/29/innotrans-2016-passenger-experience-review/#sthash.NTBHABp1.dpbs of the upper deck of the Aeroliner exhibited at Innotrans in 2016. It illustrates clearly the problem of trying to squeeze two decks into a passenger carriage built to the UK loading gauge. If introduced to Britain, I’m sure there will be howls of protest from ‘normal’ height passengers who would probably boycott the upper deck, creating overcrowding on the lower deck. Without a picture of the lower deck, I don’t know if even that is suitable for your average homo sapien.

I’m sure Today’s Railways EUROPE gave a similar scathing review of the train (or possibly it was Modern Railways), but I’ve been unable to locate it.

Clearly a double-deck train in Britain is not physically possible. Assuming the height of a class 9F loco (13ft) mentioned in my earlier post, is similar to the maximum height of a carriage, that leaves just 6ft 6in for each deck, but that doesn’t allow for the thickness of the roof and two floors. Bogies can be ignored, as with double-deck trains elsewhere, they will be under full height vestibules at each end of the carriage.

Interesting article. What I see on the continent is rolling stock determined by function and bi-level is losing out slightly to metro-style single deck articulated units, very visible in the Netherlands where series of second generation 4-car push-pull bi-level local sets have been re-engineered into attractive regional sets. The regional sets in Europe usually are double-deck and long distance sets rolling stock may be single or double deck determined by available and foreseen loading. In France this often leads to a single-deck and a bi-level set running coupled. Quite clear is that EMU or loco-hauled propulsion is very much a matter of local need: those operators who do not run freight any longer go for EMU’s, those who run freight and can employ loco’s on other duties will use push-pull.

Graham. A fascinating piece, and an entertaining read. You may be interested to know that on Jan 19, Great Western agreed to uprate the IEP bi-mode diesel engines to their full 940hp capability to keep up the maximum speed. I am not sure what that maximum speed now is. Apparently it will give the Class 800 bi-modes a similar power to weight ratio as an IC125. GW has already ordered a number of Class 802 IEP sets for Cornwall services that come complete with the fully-rated engine and larger fuel tank. The maximum line speed in Cornwall is, however, only 75mph I believe, so the extra power is needed for climbing steep embankments rather than keeping speed up. It remains to be seen if the IEP can keep up with the ageing IC125 in diesel mode.