Overcoming challenges of rail infrastructure renewal

Posted: 17 November 2016 | | No comments yet

Global Railway Review’s regular blogger Graham Ellis explores the challenges of renewing infrastructure on rail networks and provides case studies on different approaches to the task.

With the growing use of rail based metro systems in locations such Newcastle, Sheffield, Birmingham and Manchester as well as the rest of Europe, there are problems they all face, worn out infrastructure or alternatively, the need to modify track layout to meet new or amended operational requirements.

At the recent European Transport Conference held in Barcelona two metro systems gave presentations on how they had approached this need to renew infrastructure, they were the city of Nantes in France and Manchester in the UK. Both of these cities faced challenges in their infrastructure and both had different approaches to their different challenges.

Nantes Metropole

Sakina Faouzi from Nantes Metropole took delegates through the major works undertaken by the city to update the tram network. The first operational section of the tramway system in Nantes had been in existence since 1985 with later parts being completed up to 2006, so the oldest section was over 30 years old. It was found that worn rails had led to increased de-railing risks, that people could have accidents due to poor road surface condition and that cross-over layouts needing to be changed. In detailed analysis it was found that 1 minute lost in service added the need for two more trains to the daily operational requirement of the system. The cost of improvement was calculated at 7 million Euros and an extra 300,000 Euros per year in maintenance costs. With no renewal of the infrastructure then there would be a need to keep shutting the system down to allow maintenance to be carried out and that substitute options could not be reinforced.

The city, in co-operation with the operator (SEMITAN), planned the system upgrade taking into account the risk to the public, the availability of money and the need to meet urban plans. Not only was the infrastructure considered but both the rolling stock and the bus and tram garage and its maintenance buildings also received attention.

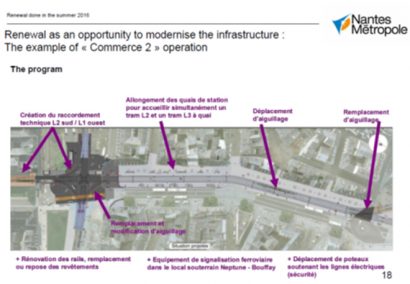

The closure of part of the system took place during the summer of 2016; two sections of work were undertaken requiring the closure (blockade) of the tracks of Line 1 in the centre of the city and between the station and the centre. One of the key installations was a link between line 1 and Line 2 because one of the tram depots was sited at the south of the city and when the central blockade was installed the trams were unable to leave the depot and by-pass the blockade. With the new link track that problem has now been overcome and future works in the central area should be able to allow trams to still operate, this was further improved by modernisation of the signalling system bring the technology right up to date.

All of the work was undertaken during the summer of 2016 and successfully completed on time by autumn 2016 and the system is now fully operational again. This was complex but remained a well planned and executed project.

Greater Manchester Metrolink

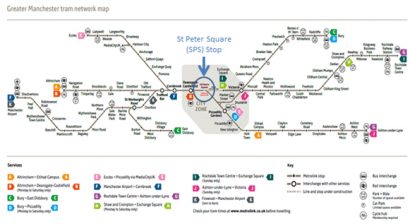

Moving across to Greater Manchester, delegates heard from David Gregory of David Gregory Transport Planning, on how the Greater Manchester Metrolink planned to close one of the major city centre junctions to allow major expansion of the system to take place. The Metrolink was opened in 1992 on the route from Bury to Altringham and has grown from the original 26 stops to the current 93.

The stop at St Peter Square, right in the centre of the city is the one place where all of the various lines converge and so to increase the flow of trams through this stop a major blockade was required but, this would have a serious effect on passenger flows into and out of the city. When the first phase of the system opened only 20 trams per hour (tph) travelled through the stop but currently the traffic requirement is 70tph and by the time the Trafford Park line is completed in 2020 the total flow will be at 80tph.

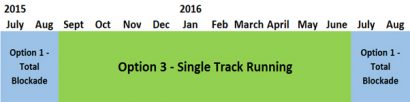

The planners were faced with a number of options, i) a total blockade for 11 months with no trams at all, ii) partial running with a stop over a 22 month period allowing a maximum of 5tph or iii) partial running with no stop allowing 10tph and again taking 22 months. In order to make informed decisions a number of models were used to forecast the implications for passengers. It was found that a total blockade would cause people to walk for longer distances and possibly overloading of the available trams at adjacent stops. Option 2 was found to be impractical and so option 3 was the closest but, could a hybrid solution be found that brought increased benefits? The answer was yes there was a hybrid solution.

What was selected was a total blockade during July and August 2015, single track running with no stops and 15tph between September 2015 and July 2016 and then another blockade between July and August 2016 as shown below.

Trams were “flighted” in threes to minimise the number of changeovers in each hour. Hence, the trams from Eccles, East Didsbury and Altrincham all had to arrive at the entry point to the single track within three minutes of each other. 15tph would reduce demand losses by 15%.

All services operated on 12-minute headways but the punctuality of the services was critical. Having 15tph meant all three lines to the south of the City Centre maintained a service through the City Centre and there was plenty of capacity for those people using services that would have to terminate short of the centre at Deansgate-Castlefield or Cornbrook, with all through services operated as double units.

Did this succeed? Well, the disruption only lasted 19 months in total with continuing tram services into and out of the city centre; apart from when the blockades were o; and I was able to test this hybrid solution during the European Bus Forum which took place in Manchester on 23rd June. I flew into Manchester airport from Southampton and followed the signs to the tram station, the tram took me from the airport across Manchester into the centre, and a very strange single track working was controlled by staff in boxes at each end of the single track working either side of St Peter Square.

It was obvious that major work was ongoing but as I had not heard of the altered workings prior to arriving in Manchester I was not unduly inconvenienced, after all I wanted to arrive in to the city centre and did so, on the tram. The new platforms at St Peter Square will see 25 tph, with up to 10 of those being double length units and once the new 2nd city crossing is added in 2017 up to 40tph per platform, with up to 50% of those being double length units, or in other words a tram every 90 seconds per direction.

St Peter’s Square – Sept 2016

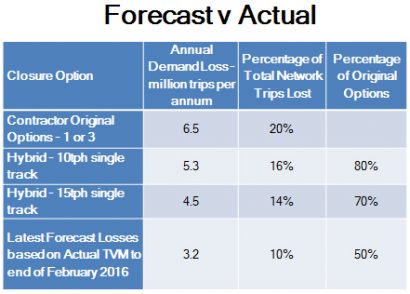

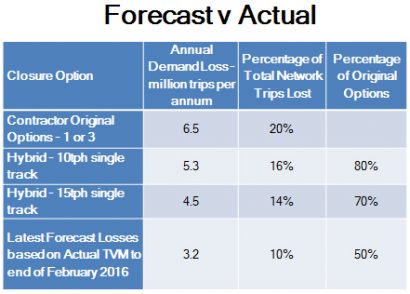

The test of the effectiveness of this project is measured by passenger loss and recovery. The table shows that the solution seems to have been highly effective and the team at Transport for Greater Manchester are to be congratulated on their foresight in achieving the outcomes shown below.

As colleagues at Network Rail will tell you there is no “good” time to carry out works on infrastructure and blockades are the ultimate last resort when no other solution is available to achieve the renewal of infrastructure.

Stay Connected with Global Railway Review — Subscribe for Free!

Get exclusive access to the latest rail industry insights from Global Railway Review — all tailored to your interests.

✅ Expert-Led Webinars – Gain insights from global industry leaders

✅ Weekly News & Reports – Rail project updates, thought leadership, and exclusive interviews

✅ Partner Innovations – Discover cutting-edge rail technologies

✅ Print/Digital Magazine – Enjoy two in-depth issues per year, packed with expert content

Choose the updates that matter most to you. Sign up now to stay informed, inspired, and connected — all for free!

Thank you for being part of our community. Let’s keep shaping the future of rail together!