How can rail stations advance to keep pace with the evolution of society?

Posted: 1 September 2022 | Clément Gautier | No comments yet

Ahead of moderating Global Railway Review’s upcoming Roundtable feature, Clément Gautier, Project Manager at the UIC, explores our understanding of precisely what a railway station is, and more importantly he details what this means for the station of 2022 and the future it will need to serve.

What is a railway station? You may be wondering why it is important to answer this question; a question that seems trivial considering that I am the Stations Project Manager at the International Union of Railways (UIC). However, after more than five years of working on the subject every day, I still find it hard to explain to people exactly what a ‘railway station’ is.

It was during a discussion with the UIC’s Director General, François Davenne, that these questions arose: What is your subject? What exactly are you talking about when you talk about a railway station?

…after more than five years of working on the subject every day, I still find it hard to explain to people exactly what a ‘railway station’ is.

This subject is something that seems to be known and understood by everybody, and, to some extent, it is. It is fascinating that in the minds of most people it is easy to recognise a railway station, new or old, operational or closed, and this is the case in most parts of the world. But, to recognise is not the same as to understand. My intention here is not to rehash the history of railway stations and rail in general, but instead to focus on 2022 and on the elements – current, new, and future – that constitute, and will constitute, railway stations over the coming years and decades.

Before embarking into the heart of the matter, I invite you to read an upcoming Roundtable discussion on this very subject; Global Railway Review is inviting players whose day-to-day work revolves around railway stations, and I will have the honour and pleasure of moderating the discussion.

What is a railway station?

You will not find a clear and precise definition of the structure and functions of a railway station here, as these vary too greatly from country to country. So where do we start? Should we define a station by its function, its location, its services, its role in the rail network or town/city, or by its manager, who may own or operate it?

A station is an interface, a place of transition where a person is transformed into a passenger the moment they enter the building (or station stop) to take a train. By virtue of this, stations are situated on a railway line.

Stations must offer the minimum conditions for the effective operation of trains and to welcome travellers, i.e. guarantee safety, security and service for passengers. Of course, in order to enjoy rail transport, the station building must be structurally connected to the transport infrastructure. To define the structure and minimum service, I suggest you look at how small stations operate in your own country.

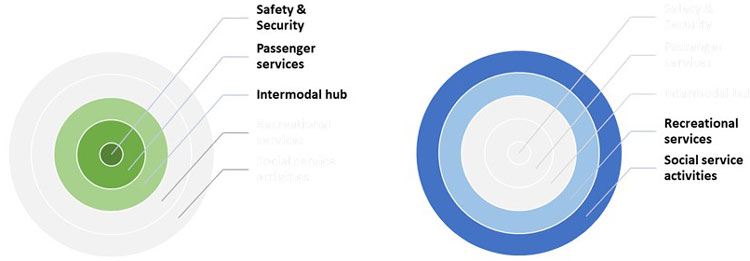

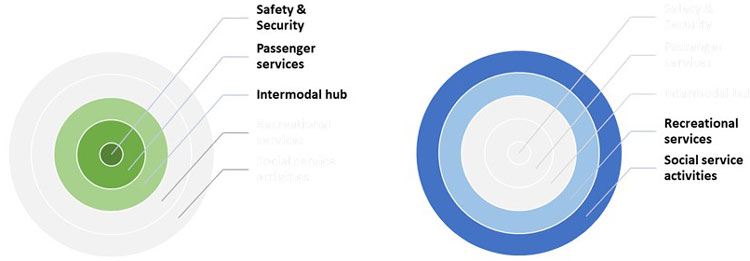

The level of services and intermodality is dependent on how much traffic the station receives (travellers and non-travellers). The management of a small station will naturally not be the same as that of a central station which handles several hundreds of thousands of people every day. As such, the higher the traffic, the more important the level of safety, security, customer services and intermodality. For this type of station, services not related to travellers are more likely to be offered, and these take the form of complementary or leisure services (cultural and sporting events), as well as services related to people (programmes to help the homeless, for example).

Daily traffic is also an element by which the role and functions of a railway station can be defined within the network as a whole. However, another question must be asked: Where does a railway station start and finish?

The management of a small station will naturally not be the same as that of a central station which handles several hundreds of thousands of people every day.

From the point of view of a simple user, the station starts from its forecourt and ends on the platform before boarding the train. To a certain extent, we rely on the continuity of the frame structure. Naturally, this perception is only true in part, and to understand why, we need to take a look at the flipside of the reality, the side of the owner and manager.

The field of competences for railway stations varies from country to country, which consequently makes understanding the station entity slightly more complex. For some, railway stations are simply property assets (Jernhusen, Sweden), for others, stations are managed by the network manager (SNCF, France), for others again, by the railway operator (NS, Netherlands), and for some, the manager is not necessarily the owner of the building (VIA RAIL, Canada). Everything depends on the perception and philosophy ingrained in each country. But what is true now will probably not be true later, as things change depending on the strategic framework laid out for decades to come.

In addition, it should be highlighted that railway stations have five major components, represented by the opposite diagram. The difficulty here is understanding each piece of this diagram and that each one can be managed by different players; the organisation that builds a station is not necessarily its owner and even less likely to be the manager. This is why I use the term ‘station entity’: to include all the elements that make up a railway station.

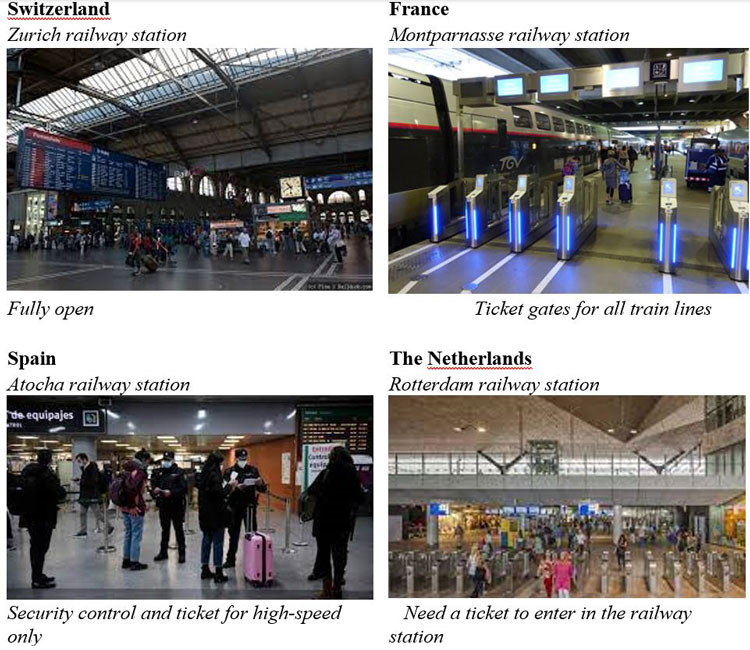

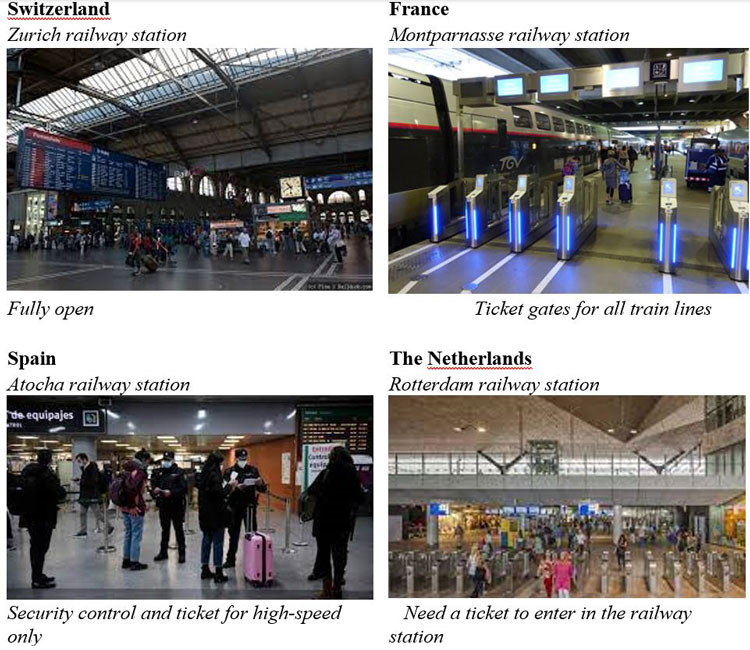

In terms of accessibility, the station entity can be completely open, as for Swiss stations, partially closed with access to specific zones requiring a train ticket (Spain, France), or even completely closed (Netherlands).

There are therefore an infinite number of cases, which once again makes it so difficult to understand and operate railway stations.

Why are railway stations so sensitive to their environment? And what can they offer?

One thing is the same for all railway stations: the need to adapt to their environment. All railway stations want and need to be capable of fulfilling the requirements of both the rail system and the urban system.

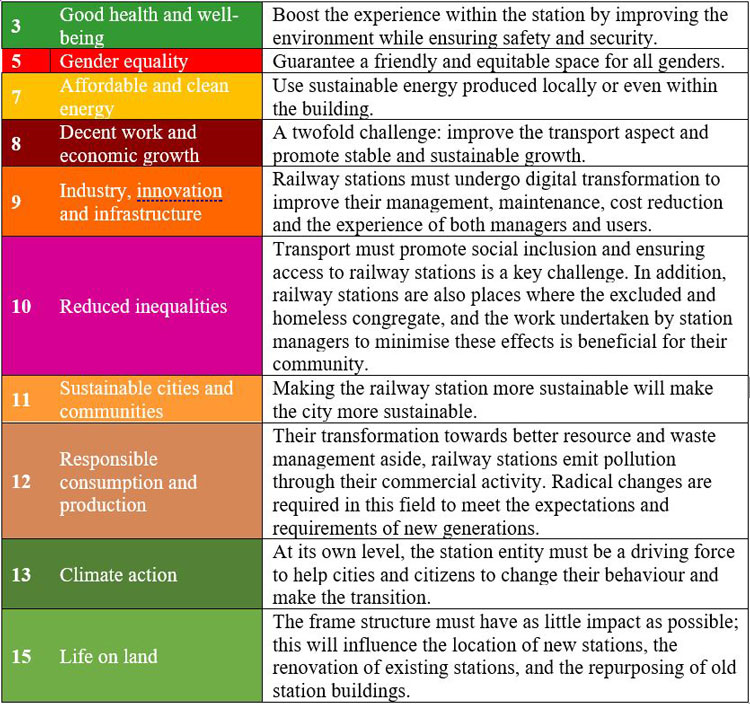

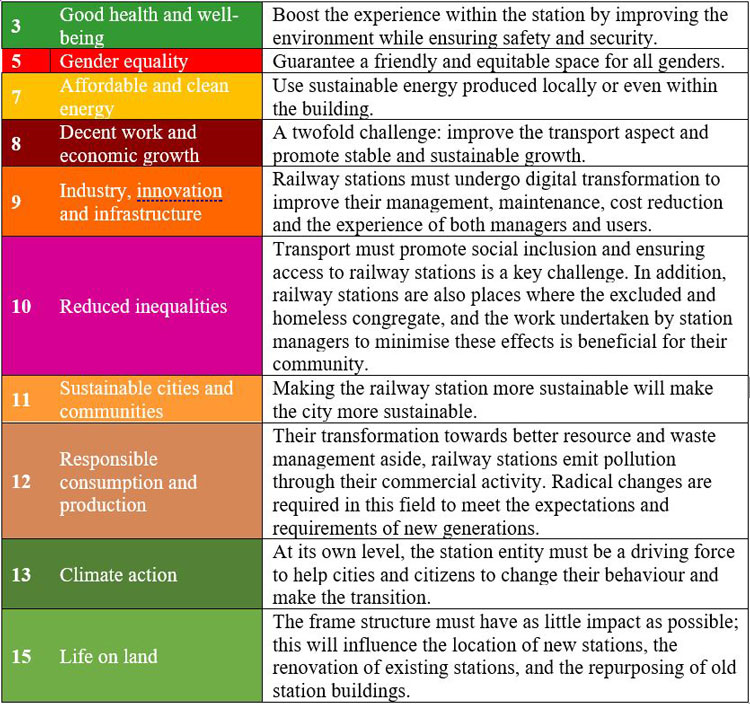

The station entity is perpetually evolving and transforming. This is again explained by its role within railway transport and within the city. The station entity is able to play a major part when it comes to global issues and particularly the objectives set out by the UN, which go well beyond these railway prerogatives. And managers are willing to step up to this challenge.

At national level, rail is seeing its significance grow year after year, with the addition of kilometres of high-speed track, the purchase of new fleets of trains and (trans)national policies promoting international transport. Rail transport is also becoming more and more competitive and attractive; the number of passengers making use of the €9 ticket in Germany is evidence enough. Railway stations are going to see their traffic increase significantly over the next few years, which will run the risk of triggering issues of safety, security and bad experiences within stations.

Railway stations are going to see their traffic increase significantly over the next few years, which will run the risk of triggering issues of safety, security and bad experiences within stations.

These new behaviours are prompted by several factors: the increase in fuel prices; the difficulty in recovering from the pandemic; wars in different regions around the world; inflation; and national policies in favour of sustainable transport modes. Technology has also profoundly changed the behaviour of players and customers, as the immediacy of needs and information makes it possible to react to meet these requirements. The problem arises when the ‘possibility’ to do something becomes the ‘obligation to do’: to be more attractive, cheaper, to have better offers, to offer a better experience, with reactive, and high-quality services. There is increasingly no room for error for station managers, without seeing their revenues affected.

How many cities, for example, have forced station managers to keep buildings open without passengers for several weeks, beyond the reality of common interest? There is no doubt that railway stations represent essential infrastructure, sometimes more for non-rail than for rail transport itself.

Station managers are aware of this and are eager to take on a more significant role than simply being the transition point between city and train, as explained by Network Rail: “We want everyone to feel welcome at our stations, which is why we’re proud to be doing our bit to help passengers access these vital products – as well as anyone else who needs them […]. Mitie and Network Rail are committed to delivering social value to maximise our positive reach and impact on the communities we serve.”. This can be seen most clearly when stations are renovated; it is common parlance to talk about renovating the station district rather than simply focusing on the building.

How can railway stations get what they need to achieve their objectives?

How do we modernise railway stations? How can we ensure we make the best decisions? There are two aspects to this: what to do and how to finance it.

The only thing that is certain today is the uncertainty and unpredictability of the future. Since 2017 and my arrival at UIC, I have had to contend with:

- The ‘Uber-isation’ of society

- The development and democratisation of tools for personal mobility (electric scooters, the solowheel, etc.)

- The global influence of new social media like TikTok

- COVID-19

- International events impacting national economies (increased fuel prices, inflation, etc.).

So many factors that have had an impact on all communities, not just European; so many factors that have disrupted the effective operation of railway stations.

So what can we do? How can a station manager manage infrastructure which is relatively immutable (major investment, heavy infrastructure) while its environment is constantly evolving? Is there a business model that guarantees the investment required to respond to international challenges and meet the above-mentioned national requirements, while taking ‘disruptive’ factors into consideration?

I’m not about to give you a lecture on the role and efficacy of PPPs (public-private partnership) when it comes to the construction and renovation of public infrastructure, as this is outside my field of expertise – though it is a subject worth exploring. Instead, I would like to take a more theoretical look at the capacity to attract funding by comparing the model for railway stations with that for airports.

Can train stations be managed in the same way as airport terminals?

In many ways, airports and train stations are similar, there are even some infrastructures that operate for both rail and air travel at the same time.

In many ways, airports and train stations are similar, there are even some infrastructures that operate for both rail and air travel at the same time. Let us start with a practical case-study: In July 2005, Paris Aéroport (Paris Airports) became a public limited liability company (corporate law) in order to attract investors to modernise the infrastructure and respond to market growth. The liberalisation of the European rail market leads us to ask the question: Would it be possible to do the same for railway stations? Would it not be beneficial for Gare & Connexions, ADIF, RFI or NMBS/SNCB to concentrate exclusively on major stations (of national and international significance), while delegating other stations of only local significance to the approval of the law. In fact, if we push the liberalisation of the market to its logical conclusion, station managers will be working with a multitude of railway operators and will have to offer services to every customer of every company. This would subsequently make it possible to reduce the money spent on small stations, with little or no commercial value, in order to concentrate on more customer-driven spaces where sizeable returns on investment make it possible to secure enough funding to transform railway stations and have a positive impact on both the railway and the city. One thing is certain, airport managers are naturally more able to innovate, invest and revolutionise the management of the building and the customer experience than is possible for station managers.

Taking an even longer view, will it be necessary for managers to have a historical or geographical attachment to the location of the management of the station? Will we see managers buying or renting the management of a station in another country? Perhaps we’ll even see station managers owning sections or contracts in other international stations (for example, ADP for Sabiha Gokcen International Airport in Istanbul, Turkey). Would it be unrealistic to imagine Saint Pancras station going public to obtain the funding needed to support all the transitions and transformations required to meet the objectives set by global public transport and governmental players?

Perhaps most of these musings will remain hypothetical, but for the moment the familiar question remains: What will the railway stations of tomorrow look like? What form will they take? What will the permanent consequences of COVID-19 be, not simply from a healthcare perspective, but also regarding the changes enforced by the pandemic? We are facing new realities which are just waiting to be uncovered.

Conclusion

This article may appear long and confused, but all the issues raised are relevant.

As a reflection of societies which are constantly evolving, stations need to mirror this evolution.

A station is an element of the (rail) network, classified by category (compared to other stations) and operated by one or more station managers. It is not only part of the railway system infrastructure, but also essential in several ways, as it is a component of the urban network into which it is unequivocally integrated, regardless of its setting, rural or urban.

Its function? To serve; to serve the railway system it hosts but also the city that supports it.

Railway stations are unquestionably essential infrastructure, defined by the different entrepreneurial, local and social services which have been established by national (or in the case of Europe, international) policy. Each station has its zone of influence defined by its capacity to attract people for rail services and other socio-economic and cultural activities. The greater its influence, the more substantial a role the station will play within all the equity borne by its manager.

As a reflection of societies which are constantly evolving, stations need to mirror this evolution. And now that the question of why has been raised, it is time to understand how this can be done. To answer this, I invite you to read very closely the upcoming Roundtable feature within Global Railway Review, which will also tackle the question “What is a railway station?”, but this time from the perspective of the players, who have a strong geographical attachment and will even know already what their railway stations of tomorrow might look like.