Railway financing – expand your scope, you’ll need it

Posted: 5 November 2020 | Helena Goetsch, Martha Lawrence | No comments yet

Martha Lawrence and Helena Goetsch from the World Bank explain that railways can tap into private sector financing for much needed investment, using a variety of instruments at sovereign, corporate and project levels. But the keys to unlocking that financing are funding and risk mitigation.

Interest in railway investment is resurging worldwide as countries try to green their transport systems, ease urban congestion and improve the safety and efficiency of passenger mobility and freight logistics. Substantial investment is needed – the McKinsey Global Institute estimates that $300 billion a year through to 2030 will be required. This is more than governments alone can afford, especially now, when they are fighting the coronavirus pandemic. So, from where will the money come?

Railways are increasingly turning to the private sector for needed investment funds. India, for example, has just launched a process to allow private companies to invest in rail rolling stock and operate passenger train services on over 150 routes. The good news is that railways can tap into private sector financing using a variety of instruments at the sovereign, corporate and project levels. The keys to unlocking that financing are funding and risk mitigation.

Funding

Funding is the railway’s revenue stream. In contrast, financing is money raised using instruments such as bonds, stock, loans and leasing. Funding is very important, because financing is not free money – it must be paid back with dividends or interest in addition. Typical sources of funding are passenger ticket sales, freight operations, government subsidies or other revenues from leveraging railway assets, such as: Advertising in passenger coaches; leasing of space in stations; leasing the right-of‑way for communications cables; using the electric power supply system to also deliver commercial or residential power; or selling the air rights above rail yards or active tracks for the building of profitable real estate. Funding must cover the railway’s operating costs and still have enough money left over to pay back any financing.

Sometimes, the expected future funding will not be enough to cover costs and pay for needed investment – the railway is then left with a ‘funding gap’. To close the gap, the railway can:

1. Reduce investments and/or operational costs

2. Increase revenue by expanding profitable traffic and/or obtain subsidies from the government for providing loss‑making services.

The World Bank works with many railways to bring their funding into balance with their expenditures, so there is enough surplus to raise financing. For example, the World Bank has supported high-speed rail market development in China; development of freight markets in India; and staff and organisational restructuring in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union.

Risk

Investors providing financing to railway companies or projects will evaluate the risks that they will not be able to repay the debt or provide a return on the equity. This risk perception will be built into its cost of financing. The riskier the investment, the higher the rate of return the private sector investor will require.

The two main risk components evaluated are usually the governance of the railway sector as a whole and the corporate governance of the railway company or project entity. On sector governance, the private investor wants to know whether the government’s policies are reliable or might be changed in a way that negatively affects cash flow. On corporate governance, the investor will look at the governance structures and whether they ensure that the railway takes commercial decisions that support its ability to provide a return on investment.

To keep the cost of financing low – and, indeed, to access private sector financing at all – these governance risks need to be addressed: A welcoming business environment, clear and consistently applied transport policies, as well as sound corporate governance. For example, through a competent and independent Board, external auditors and transparent reports are key to reduce those risks.

Financing

Financing can be raised from the private sector, based on the funding and financial strength of a government, a corporation or a project.

Sovereign financing

The largest pool of financing raised worldwide is sovereign financing – financing raised by or through government. Government debt worldwide amounts to more than $69 trillion, and adding sovereignguaranteed debt would increase this total. A small portion of sovereign financing is official development assistance, including loans from development financing institutions, like the World Bank – currently, the World Bank is actively involved in 12 railway investment loans in 11 countries, with an overall portfolio of $3.5 billion. Sovereign financing is typically the cheapest financing, but is not always available to the railway because governments have many priorities. This is particularly the case now, with governments seeking to repurpose their borrowing capacity to COVID-19 relief and recovery.

Corporate financing

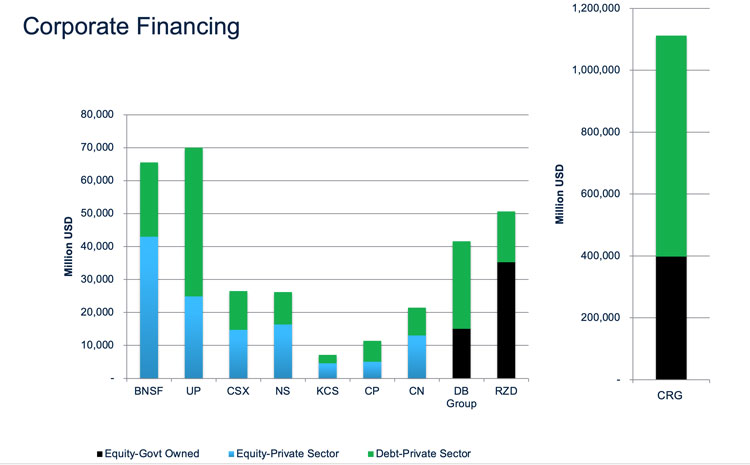

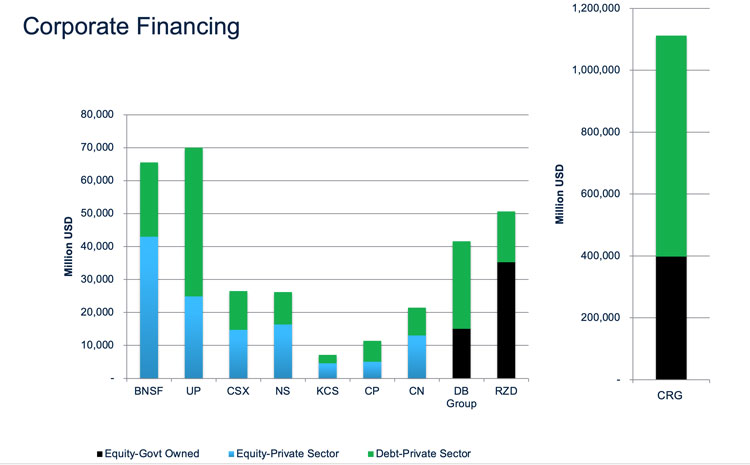

A second, smaller, but still significant pool of financing is corporate financing. Corporate financing is raised based on the funding and financial strength of the company. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) reports that corporate debt amounted to $13.5 trillion in 2019. Railways, as government-owned entities, often overlook corporate financing, but it deserves greater attention. Figure 1 shows examples of railways that raise corporate financing. Some of them raise all their financing from the private sector. The first seven companies, all Northern American freight companies, have raised all of their financing – both debt and equity – from the private sector.

Others – such as Deutsche Bahn (DB), Russian Railways (RZD) and China Railway Group (CRG) – mix sovereign and corporate financing. Their stock is owned by the government, while debt is borrowed from the private sector. Counting both debt and equity, the first nine railways have $270 billion in private sector financing. Including CRG, which is an order of magnitude larger than the others, the number rises to $985 billion.

In every case, these railways are able to raise debt (and some of them equity) in capital markets because investors view them as credit worthy. Investors look at their traffic, revenues and costs and make the judgment that the railway will be able to pay the interest and principle on debt – or dividends on the stock – in future years, with sufficient probability that they are willing to provide financing to the railway.

Project financing

The last pool of financing is project financing. It is based on the funding and financial strength of the project. Project financing is typically the most expensive type of financing, because investors have recourse only to the project for repayment of the money invested plus returns on their investment. Nonetheless, many projects are financed on a purely private sector basis.

Public Private Partnerships

When government and the private sector carry out a project jointly, the project is a Public Private Partnership (PPP). In emerging markets, infrastructure project financing of PPPs has raised just over $10 billion per year, on average, in recent years. PPPs are complex to structure and oversee. Their value comes from harnessing private sector knowhow and incentives for efficiency and market development. Also, PPPs sometimes allow the railway activity to be ringfenced and somewhat insulated from the political environment, making it possible for the railway to operate more commercially. The World Bank Group has supported numerous railway concessions in Latin America and Africa and is currently working with clients worldwide to develop PPP programmes based on assets, such as stations and loading facilities.

Loans, bonds, stocks and leases are typical financing instruments. Sovereign entities typically use loans and bonds to raise financing, and investors judge the risk of these instruments based on the financial strength of the country. Corporate entities use all four instruments and investors judge the risk of these instruments based on the financial strength of the company. Corporate stocks and bonds are often traded on exchanges. This makes them more attractive to investors, because they can easily exit the investment. PPPs are not a financing instrument; they are a project delivery mechanism with financing. PPPs can access all four financing instruments based on the financial strength of the project. The stocks and bonds of PPPs are usually not traded on public exchanges. The World Bank has recently offered a free e-learning on its Open Learning Campus that explains these concepts in more detail.

Conclusion

With the public expenditure on railways currently limited by the coronavirus pandemic, railways must look beyond sovereign financing to meet their investment needs. By making railways financially viable with a sound basis of funding, financing instruments – such as loans, bonds, leases and stocks – can be accessed through corporate and project financing. The World Bank sees our clients are rising to the occasion – first, with programmes to address public needs and keep their employees and customers safe and, second, with measures to increase funding, manage costs and tap non‑traditional sources of financing.

Global Railway Review Autumn/ Winter Issue 2025

Welcome to 2025’s Autumn/ Winter issue of Global Railway Review!

The dynamism of our sector has never been more apparent, driven by technological leaps, evolving societal demands, and an urgent global imperative for sustainable solutions.

>>> Read the issue in full now! <<<