The Port of Piraeus – Opportunity for Railways in South East Europe?

Posted: 8 September 2016 | | 3 comments

Aleksandar Bauranov, transportation engineer and research associate, discusses the opportunity of utilising the Port of Piraeus in Greece to cut rail freight times to South East and Central Europe.

Chinese state-owned shipping companies, along with several East Asian corporations, have marked the Port of Piraeus as a new logistics hub of Europe. China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO) in 2009 won the 35-year concession for the two of three port terminals and in January 2016 formally acquired a 67% share for €370 million. Furthermore, the company has announced another €350 million investment in the next five years, increasing the port capacity from 1 million to 7 million TEUs1. [1]

A reliable indicator of the future traffic potential is the Hewlett-Packard (HP) decision from 2013 to relocate a major part of its distribution operations from Rotterdam to Piraeus, and use the rail transport from Piraeus for distribution to the Balkans, Hungary, and the Czech Republic [2]. East-Asian companies like ZTE, Samsung Electronics, Dell, Lenovo, and LG have also expressed interest to use Piraeus as a gateway to South East and Central Europe.

Railway Corridor X meets the potential demand but is inadequately equipped. In the competition with the Corridor IV and the trucking companies, it will be increasingly difficult to attract new rail freight. Plagued by the poor infrastructure and long border-crossing procedures, the corridor is in dire need of investments and better policies.

Estimated trade in 2016 between Central Europe2 and Asia is 1.8 million TEUs, and Southeast Europe3 and Asia around 0.9 million TEUs [3]. The cargo coming from Asia is shipped to one of the Mediterranean or North European ports where it is reloaded to a smaller ship, which then transports it to the final destination (transshipment). Alternatively, cargo is reloaded to a rail or truck and arrives at the final destination by land (transit). The Port of Piraeus is not reaching this market. Out of this year’s target of 3.3 million TEUs, around 2.1 million will be transshipped to the ports in Spain, North Africa, and the Middle East, 1 million unloaded in Greece for the local market and only 0.2 million TEU is the transit traffic going to the Central and Southeast Europe [3].

COSCO and Trainose, a Greek railway operator, are very interested in becoming a player in this 2.7 million TEUs market. Their goal is to integrate the port and rail operations and provide quick and seamless shipping to the hubs in Hungary and Czech Republic. Undoubtedly, Port of Piraeus has a sufficient capacity to service the entire market. However, the rail infrastructure is not up to speed, making the ports in the Adriatic Sea and the Black Sea more viable routes.

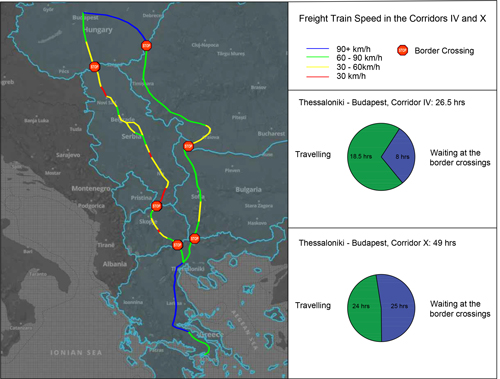

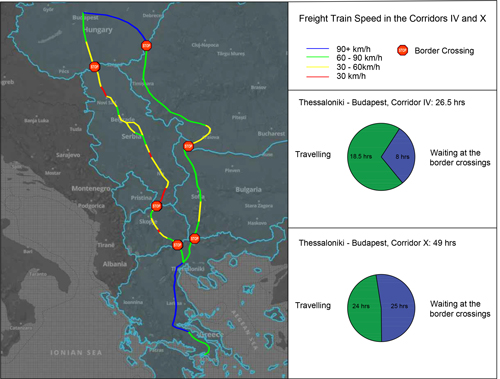

Future plans for railways in South East Europe

The ways to reach this market is by truck, by rail via Pan-European Corridor IV or rail via Pan-European Corridor X. Currently, out of 0.2 million TEUs of the transit traffic, only about 25% is shipped by rail. The European Union has recognized the opportunity and included Pan-European Corridor IV in the network of nine core TEN-T corridors. Romania has secured €2.9 billion for modernization, electrification and construction of the second track for the 490km section from Arad to Calafat, achieving speeds of 120km/h for freight trains by the year 2020 [4]. Similarly, Bulgaria will receive €1.6 billion from the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and Cohesion Funds for modernisation of the same corridor [5]. The plan is to cut the Thessaloniki – Budapest travel time to 14 hours [5] and become an obvious choice for the shipping companies. At the current state, a large portion of the Corridor IV railway infrastructure is a single track with operating speeds between 60 and 70km/h [5]. Notwithstanding the EU membership, the countries on this stretch of the Corridor IV still face an issue with the border procedures. The waiting time on the Greece/Bulgaria border is around 3.5 hours, Bulgaria/Romania around 2.5hrs and Romania/Hungary up to 2 hours. The waiting time is the result of slow operational procedures, such as changes of locomotive and inadequate staffing. According to the EU strategy for the corridor, the waiting times will be reduced to 20-30min by 2020 and ultimately annulled by 2025 [5].

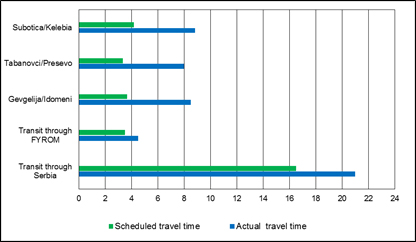

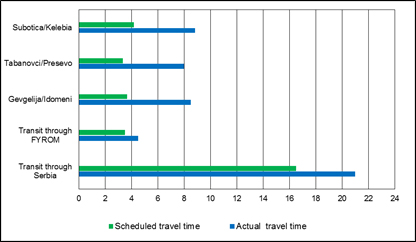

Corridor X, although 300km shorter than its eastern neighbour, is currently not a viable option for the long haul transport. Extended travel times, inadequate maintenance, sluggish speeds and on-going development of road infrastructure parallel to railways have contributed to the decline in the cargo transport. Furthermore, waiting time on the borders is on average eight hours [6] (Figure 1). Each train is stopped twice per border, where it goes through lengthy customs and operational procedures. Further organisational problems, such as extra shuttle services between border stations, lack of coordination and communication between the operators and legislative differences boost the waiting further.

Figure 1. Waiting time per border crossing, source: [6]

In total, the travel time from Thessaloniki to Budapest can be as high as three days. On average, it lasts 49 hours (see Figure 2), half of the time spent at the borders. Average commercial speed is 22 km/h, and average running speed is around 35 km/h [6].

Figure 2

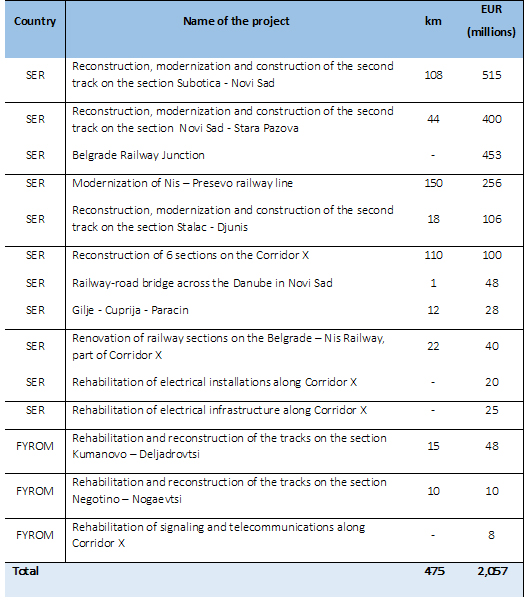

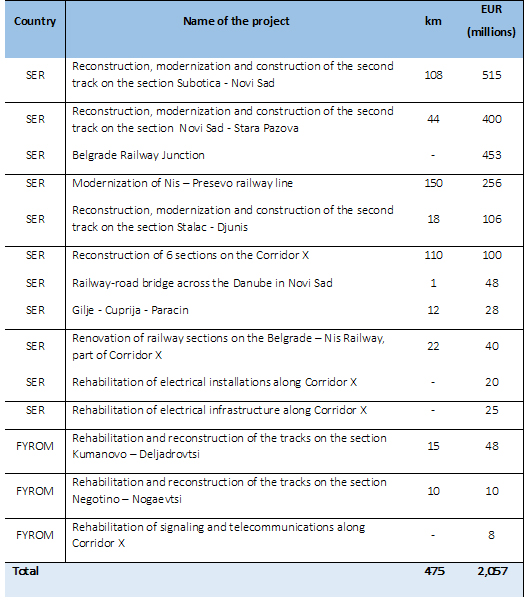

The authorities in Serbia and Macedonia have recognised the problem and started a number of projects to improve the condition of the infrastructure. In Serbia, the investments in rail infrastructure in the next ten years should reach €1.9 billion [7] for rehabilitation or reconstruction of approximately 460km of rail infrastructure, which is around 85% of the length of Corridor X (the north-south branch) in Serbia.

Planned investments on Corridor X

Expected speeds of freight trains after modernisation will be 80 or 100km/h, depending on the section.

Smart operational improvements for rail freight

The planned infrastructure improvements should save around 8 hours of travel time through Macedonia and Serbia on account of increasing the design speed of the tracks. However, this is not enough to compete with the 14 hour travel time on the Corridor IV. In order to take a share of the freight traffic, additional reforms must be implemented. The biggest time savings can come from smart operational procedures:

- Flexible timetable planning

In 2014, the inaugural COSCO train transported goods from Piraeus to the Czech Republic via Macedonia, Serbia, and Hungary. After weeks of planning, Serbian Railways (infrastructure operator) managed to shorten the travel time for 5 hours and border waiting time for 3 hours. This reduction may be achievable for the current traffic of one COSCO train per week, but the higher frequency in the future will not allow these manual optimisations.

GPS tracking of locomotives and appropriate timetable planning software could shorten the journey by making instantaneous changes and prioritising the incoming freight traffic. Based on the experience of the inaugural COSCO train, it is safe to assume that the software could cut travel times on a regular basis by 4 hours. The installation of GPS devices, purchase of software and training of staff costs around €2.5 million.

- Improvement in communication to ensure availability of locomotives

On average, waiting for a locomotive or a train driver amounts to 2 hours per border. Better communication could cut the time to 30 min.

- Implement a one-stop shop

Currently, all the border procedures are repeated twice. By implementing a Framework for Border Crossing Procedures proposed by the World Bank, or similar agreement, the waiting time could be cut in half. The prerequisites for the implementation of such agreement are changes in the regulatory legislation.

- Perform customs formalities at origin and destination stations if feasible

Altogether, it is possible to cut the border waiting times by up to 16 hours, and travel time by 4 hours, by implementing “soft” procedures for a fraction of cost of the planned investment.

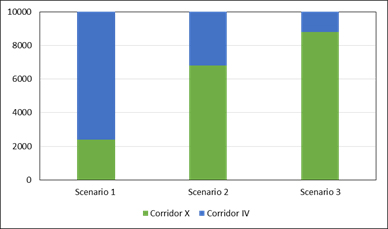

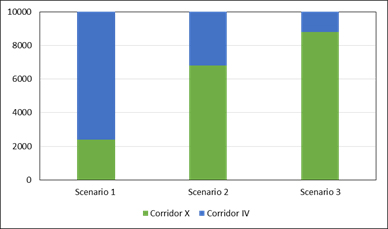

COSCO and HP agreed to run 10,000 trains (equivalent to 700,000 TEUs) per year from Greece to the Czech Republic by 2020. By taking into account the plans and improvements on the both networks, it is possible to predict the traffic split between the two corridors (Figure 3). For the purpose of the analysis, it is assumed that the travel time on the Corridor IV is 14 hours, and entry prices for both corridors are same as today (Corridor IV is more expensive for about €5000 per train). The analysis looks at the three scenarios: Corridor X has undergone only infrastructure modernisation for Scenario 1, enhanced border-crossing procedures for Scenario 2, and both for Scenario 3.

Figure 3: Traffic shares for the year 2020

‘Infrastructure investments alone will not suffice’

It is evident that the infrastructure investments alone will not suffice. If the operators on the Corridor X manage to reduce the travel time below 30 hours, they can take the majority of traffic. The revenues that they will receive are €29 million for Scenario 1, €81 million for Scenario 2 and €105 million for Scenario 3. This is a great opportunity, given the fact that the annual budget of JSC Serbian Railways is €220 million [8], half of it being government subsidies.

All things considered, long period of negligence and under investment has created a new reality for Corridor X. The European Union has initiated a strong development of the neighbouring routes, and Corridor X is becoming an increasingly irrelevant factor in the international trade. Luckily, Chinese investments in Greece present an unexpected opportunity to catch-up with the development and re-establish itself as an important partner in the European transport market. The Governments of Serbia and Macedonia have a short window of opportunity to make the sweeping structural reforms – both in infrastructure and legislation, procedures and operations, and they need to do it by 2020.

1 One TEU (Twenty-foot equivalent unit) represents the cargo capacity of a standard intermodal container, 20 feet (6.1m) long and 8 feet (2.44m) wide.

2 Austria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia and Moldavia

3 Bulgaria, F.Y.R.O.M., Turkey (European), Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Romania, Serbia and Montenegro and Slovenia

- National Bank of Greece – Container Ports: An Engine of Growth, Sectorial Report, April 2013

- Frans-Paul van der Putten – Chinese Investment in the Port of Piraeus, Greece: The Relevance for the EU and the Netherlands, Clingendael Report, February 2014

- Piraeus Port Authority S.A. – Annual Financial Report, December 2015

- European Parliament, Directorate-General For Internal Policies Policy Department B: Structural And Cohesion Policies – Romania’s General Transport Master Plan and Rail System, 2015

- European Parliament, Directorate General For Internal Policies Policy Department D: Budgetary Affairs – The Results and Efficiency of Railway Infrastructure Financing within the EU, September 2015

- HaCon Ingenieurgesellschaft mbH – The CREAM Project – Technical and operational innovations implemented on a European rail freight corridor, July 2012

- Ministry Of Construction, Transport And Infrastructure Serbia – The book of infrastructural projects in Serbia, 2015

- Serbian Railways – Financial Report 2015

|

Biography Aleksandar Bauranov graduated from The Faculty of Civil Engineering, University of Belgrade, and obtained a Master’s degree in Transportation Engineering at the University of California Berkeley in 2013. Prior to his current position as a transportation engineer at Simproject, Novi Sad, Aleksandar was a lead researcher at NEXTOR, Berkeley, and a visiting transport researcher at the Monash University, Melbourne. |

Stay Connected with Global Railway Review — Subscribe for Free!

Get exclusive access to the latest rail industry insights from Global Railway Review — all tailored to your interests.

✅ Expert-Led Webinars – Gain insights from global industry leaders

✅ Weekly News & Reports – Rail project updates, thought leadership, and exclusive interviews

✅ Partner Innovations – Discover cutting-edge rail technologies

✅ Print/Digital Magazine – Enjoy two in-depth issues per year, packed with expert content

Choose the updates that matter most to you. Sign up now to stay informed, inspired, and connected — all for free!

Thank you for being part of our community. Let’s keep shaping the future of rail together!

I saw that you mention an agreement between COSCO and HP for 700.000 TEU’s from Piraeus Port to Czech Republic. Is not this number relatively high for a specific destination only or was it written by mistake and the number is smaller? I am asking you this, because at the moment rail cargo from Piraeus Port is much lower and it seems to me a little bit difficult to rise that much, inside three years. Thank You very much.

There have been some talks about it between the Chinese, Serbian and Hungarian politicians, but it seems that will not have a huge impact on the travel time, since a lot of time is spent on the borders.

There are rumors about a second track and at least a 120-160 (??) km/h speed of traffic between Belgrade and Budapest with an investment financed by a favourable Chinese loan. If it bacame the reality the chances for the Xth corridor would be more viable.