Addressing the twofold objectives for small train stations

Posted: 11 July 2022 | Clément Gautier | No comments yet

Clément Gautier, Project Manager at the UIC, explains what challenges infrastructure managers face in operating small stations and explores the opportunities available to ensure they are utilised efficiently.

What is a small station?

For a long time, infrastructure managers have tried to find a common term to define a ‘small station’ and establish a list of priorities and action plans. However, the facts and figures of infrastructure managers differ, and as a result, it is almost impossible to make international comparisons between ‘small stations’. Consequently, it would be more accurate to speak of ‘smaller stations’. Nevertheless, for ease of expression, we will keep using the term ‘small station’.

There are four common denominators of all small stations worldwide:

- The capacity of the station manager to allocate a certain level of resources (same per cent) to these small stations, whether in financial terms (investment for rehabilitation or transformation, day-to-day management of the building in the broad sense, etc.) or in terms of human resources (staff per month on site, site supervisor, security guard, etc.)

- Low passenger rates and train frequency (in a percentage regarding the domestic market)

- No retail opportunities

- Strong sense of belonging for local citizens. Marc Augé, a French anthropologist, has perfectly highlighted the opposite phenomenon in large public spaces such as main/big railway stations: the ‘non-place’ refers to anthropological spaces of passage where humans remain anonymous, and which do not have enough meaning to be considered as ‘places’ in their anthropological definition.

How important are small stations to infrastructure managers?

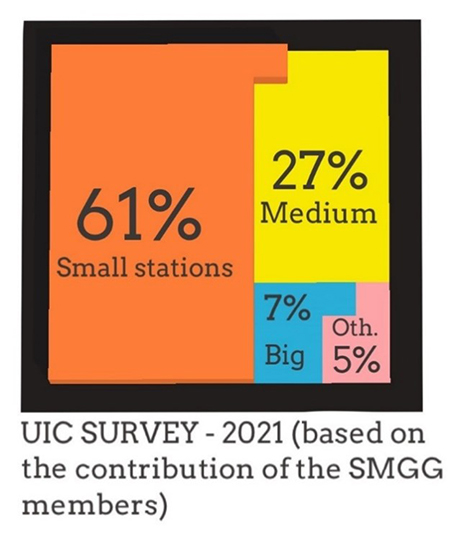

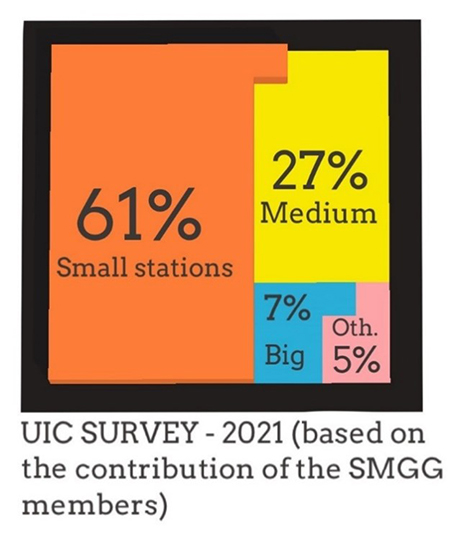

According to the 2021 UIC Station Managers survey, 61 per cent of existing stations can be defined as being small stations.

This article focuses on existing railway stations, not new ones. In fact, the biggest challenge for infrastructure managers regarding small stations is to adjust to the on-going train transport demand with existing assets. Existing small stations are, for the most part, historical and heritage buildings that cannot be transformed or removed without negative impacts.

Specific needs and expectations regarding small station assets

Small stations are supposed to be the transition phase between the city and the rail network, or at least, this was their primary function one century ago: the gateway to the countryside. Nowadays, local actors and citizens define small stations as bridging the gap between rural areas and the national network.

The economic model of stations is particularly difficult to define and to balance, as it is partly dependent on:

- The rail transport service (destination, frequency, type of service offered)

- Its geolocation (in the national network, in the country or in the city)

- Its connection with other transport infrastructures and modes of mobility (tramway, buses, taxis, metro, bicycle, car parking, etc.).

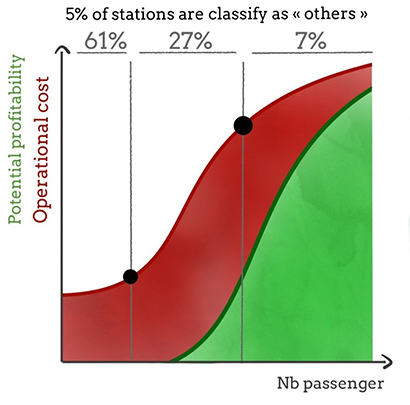

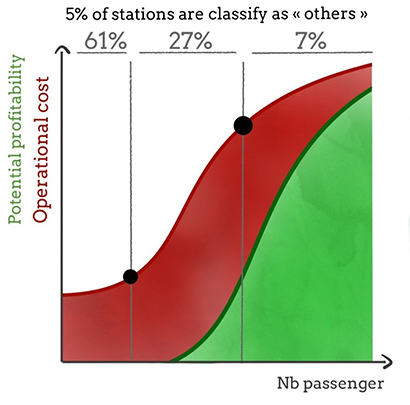

Not surprisingly, the cost of maintenance and operation of smaller stations is much lower than for the world’s major stations, but none of the smaller stations have the capacity to generate much profit. Even for larger stations, it is difficult to break even, as the fixed costs are too high for infrastructure managers. Private companies who want to develop a business addressed exclusively to passengers also face the same issues.

Is this the end for small stations? Should they all close their doors?

Faced with these difficulties, managers are led to consider another model: digitalising the management of small stations to reduce costs. Operating a building remotely can reduce the cost of operating the asset. The Smith Falls station (Ontario, Canada), managed by VIA Rail, opens 60 minutes before trains arrive and stays open for 30 minutes after they leave. But, it requires considerable investment in terms of square footage and passenger traffic, especially without the potential commercial activity that can generate a minimum of profit.

A model based solely on passenger experience and profit capture is therefore not viable. DSB (the Danish infrastructure manager) has chosen to offer a stronger territorial anchorage not only to passengers, but also to citizens. Without claiming to be profitable, DSB has transformed unused assets into spaces of conviviality, providing social connection and players in the local economy. The objective is therefore twofold: to guarantee the safety of a building (renovated and staffed), while providing a service to the community. Ulrik Harms-Bauer, Head of Business Development and Services at DSB, and his team recently worked with the municipalities of Haslev and Rungsted to use their station spaces as a ‘living room’ (‘Stationsstuen’), a Dutch concept inspired by the ‘Huiskamer’ concept. The experience of passengers is made warmer thanks to a new waiting room, which at the same time improves the feeling of security. The ‘living room’ can also be accessed by any inhabitant of the city, meaning that these places are facilitators of social connection.

The ‘living room’ concept for a small station from DSB provides passengers with a warmer experience thanks to a new waiting room which at the same time improves the feeling of security. Credit: LinkedIn, Ulrik Harms-Bauer.

The ‘living room’ concept for a small station from DSB provides passengers with a warmer experience thanks to a new waiting room which at the same time improves the feeling of security. Credit: LinkedIn, Ulrik Harms-Bauer.

The railway station as a value creator, a model not based on the profitability principle

The business model for small stations is to therefore minimise costs and create new functions to attract a wider range of diverse customers and, potentially, additional funding

Because of the special attachment of rural people to their small stations, infrastructure managers can, and should, play an additional role that was not in their original prerogative, but is nevertheless part of some unspoken moral contract. The smaller the city, the more important the station is within the city. Consequently, local actors, whether public or private, administrative or associative, wish to keep the station open as much as possible. As urbanisation affects the socio-economic activity of small towns, vital services are becoming increasingly rare. Thus, many towns that share commercial and administrative services often set these up in the empty spaces of small stations.

The Société nationale des chemins de fer français (SNCF) has been working for several years on various national programmes. After an inventory of its buildings, the company launched a call for expressions of interest to use the empty spaces within its stations: and so the 1,001 stations project was born. This initiative ensures that the SNCF’s demand to use its spaces is met and that potential offers (requests for development of activities within stations) are considered. Today, the SNCF has launched the second phase of the project: ‘Place de la gare’. Like DSB, the SNCF has been proactively participating in the renovation of these spaces for functions other than the management and reception of passengers.

However, this kind of initiative works on a case-by-case basis and is not always easy to set up, even if all the players are moving in the same direction. Before the implementation of these two projects, the SNCF tried its hand at ‘3rd places in stations’, the objective of which was to repurpose empty spaces by co-financing their transformation to create co-working spaces managed by private companies. This national project was difficult to implement for two reasons: the difficulty of implementing a specific global policy at local level and the gap between people’s habits and a solution that was too prescriptive.

Nevertheless, these experiences have led to the SNCF’s success with the two projects above.

The growing role of community and cultural aspects

Associations do have the right to take over part of a station. Countries such as England, where the feeling of belonging to a community is particularly strong, have been able to take advantage of station areas. The Community Rail Network (CRN), whose aim is to engage communities with the railways, has developed several social, cultural, and sporting initiatives to familiarise people with the railways and to use empty station spaces as community centres. The station therefore plays a strong role in social inclusion. CRN has worked with nature lovers to introduce bee habitats around stations, or with local musicians to improve the confidence of socially excluded people. This kind of community engagement is beneficial in many ways, making the station a place of life which is used on a daily basis and ultimately, reinforcing the role of the train as a primary mode of transport.

The small station has a twofold objective: local rail service and value creator for citizen.

OUT NOW: The Definitive Guide to Rail’s Digital Future

The rail industry is undergoing a digital revolution, and you need to be ready. We have released our latest market report, “Track Insight: Digitalisation.”

This is not just another report; it’s your comprehensive guide to understanding and leveraging the profound technological shifts reshaping our industry. We move beyond the buzzwords to show you the tangible realities of AI, IoT, and advanced data analytics in rail.

Discover how to:

- Optimise operations and maintenance with real-time insights.

- Enhance passenger services through seamless, high-speed connectivity.

- Leverage technologies like LEO satellites to improve safety and efficiency.

Featuring expert analysis from leaders at Nomad Digital, Lucchini RS, Bentley Systems and more, this is a must-read for any rail professional.

Related topics

Infrastructure Developments, Operational Performance, Passenger Experience/Satisfaction, Station Developments

Related organisations

Danish State Railways (DSB), International Union of Railways (UIC), SNCF, The Community Rail Network (CRN), VIA Rail Canada